Consortium

About us

Welcome! This landing-page has been set up to provide extra information for grant referees. Various research proposals will have different titles, and be drafted by different members, but if they direct here then it means that the proposed work is relevant to our team. We are building a scalable infrastructure for developing and constraining models of new bosonic degrees of freedom in cosmology. Below, you can find information about who we are, how we are looking for funding, and the nature of the proposed science.

Members and personnel

Dr. Will Barker

[pending confirmation]

[pending confirmation]

[pending confirmation]

[pending confirmation]

[pending confirmation]

Governance and funding

Why are we formalising?

The collaboration is being established as a non-profit legal entity to overcome the operational and legal limitations of an informal network. This structure is a prerequisite for directly accessing critical European programs. Formalization also introduces essential governance, allowing us to enforce intellectual property management, licensing policies, and contribution agreements.

How are we formalising?

The approach to legal recognition depends on the host country. In turn, the choice of host country is contingent on successful outcomes in the 2025-26 funding round, which will provide the necessary starting grants. The candidate hosts listed below either offer suitable grants at the national level, or offer relevant institutionalised expertise for our research programme.

Science products

Lay summary

We are living in an era of precision cosmology, where the Universe is being observed with unprecedented accuracy. This has led to the discovery of phenomena that cannot be explained by our current understanding of physics, such as dark matter and dark energy. Even when these phenomena are combined into an effective model (the dark-energy/cold-dark-matter model, or $\Lambda$CDM), there appear to be tensions between different measurements of the same parameters. Undiscovered particles are among the most popular hypothetical solutions to these puzzles, especially particles that are very light and weakly interacting.

Broadly speaking, such particles could be of the kind associated with forces (bosons) or matter (fermions). Bosons come with many different levels of complexity, corresponding to their quantum spin: gravity is mediated by a spin-two graviton, the electromagnetic force is mediated by a spin-one photon, and the Higgs boson is a spin-zero particle. As a general principle, the fewer the particles and the lower the spin, the simpler the theory is to develop and constrain: this understandably skews the literature towards studying small numbers of spin-zero particles. Given the wealth of observational data that is available now and coming in the near future, it is important to explore the full range of possibilities.

Over the last couple of years, we have developed a software framework and associated analytic techniques for developing theories with arbitrarily complicated bosonic particles. So far, this framework has been successfully calibrated against a large catalogue of relatively niche theories. We are now ready to scale up and let the data guide the search for new physics.

The public version of the software is designed to search for models by getting supercomputers to solve algebra problems. For a data-driven version, we are converting these algebra problems into numerical ones, which scale much better to more complicated theories and facilitate data comparison. The theoretical challenge is to get stable, light particles, whose small masses are not spoiled by quantum corrections. The empirical challenge is to constrain such models using as many observational domains as possible. The current datasests we are using rely on observations of spinning black holes, pulsars, and gravitational waves. In the near future, we hope to employ the microwave afterglow of the big bang and the large-scale distribution of galaxies in the Universe.

Technical whitepaper

Introduction

Particle dark matter, along with many ultraviolet scenarios, suggest that additional low-energy degrees of freedom remain to be discovered. In a basic scenario, bosonic fields on Minkowski spacetime will form a perturbative low-energy expansion \begin{equation}\label{EFTLag} \mathcal{L}=\Lag+\sum_{n=5}^{\infty}\sum_i\frac{\MAGG{n}{_i}\OperatorO{i}{n}}{\L^{n-4}},\end{equation} whose validity may be limited by the scale \(\L\). Where perturbation theory holds, it is exclusively the quadratic part of \(\Lag\) which determines the particle spectrum. In addition, it is the symmetries of this quadratic sector which allow all the higher-order interactions to be determined through a perturbative bootstrap, regardless of renormalizability. In principle, a more general embedding theory may motivate interactions which violate this procedure, but these usually incur radiative corrections which lower the cutoff.

The picture in \(\ \eqref{EFTLag}\ \) successfully describes all the fundamental bosons that are currently known to exist. In this way, linear gravitational waves give rise to fully non-linear gravity. Allowing for internal symmetries, the Maxwell and Klein–Gordon theories give rise to the Yang–Mills and Higgs sectors.

It is thus natural to treat \(\ \eqref{EFTLag}\ \) as an infrared foundation for the dark sector, but this admits a truly vast landscape of models. Even when restricting to bosonic fields without internal symmetries, the space of possibilities grows quickly with the field content. The consistent case of multiple rank-two fields was worked out relatively recently in the form of dRGT gravity. For fields of higher rank, the picture remains unclear, and connects to the long-standing problem of higher-spin interactions.

In fact, for most field configurations (excepting countably many special cases) even the free unitarity remains unknown, due to the sheer number of spin states that can be packaged into Lorentz tensors. By convenience of design, this problem is not apparent in many popular scenarios beyond the standard model, though it plagues extended theories of gravity. We are not aware of any physical reason why the dark sector should be restricted to simple field content, and a theory-agnostic approach which takes advantage of precision cosmology observables must confront this issue head-on.

Numerical polology

The formal algorithm for computing the free particle spectrum and associated unitarity of \(\ \eqref{EFTLag}\ \) has been known since the work of Van Nieuwenhuizen and Sezgin (Van Nieuwenhuizen 1973; Neville 1978, 1980; Sezgin 1981; Sezgin and Nieuwenhuizen 1980; Kuhfuss and Nitsch 1986; Karananas 2015, 2016; Mendonça and Schimidt Bittencourt 2020; Percacci and Sezgin 2020; Marzo 2022a, 2022b; Mikura, Naso, and Percacci 2023; Mikura and Percacci 2024), but the technique is computationally expensive. Computer algebra implementations have recently been developed (Lin, Hobson, and Lasenby 2019, 2020, 2021; Lin 2020; Barker, Marzo, and Rigouzzo 2024; Barker, Karananas, and Tu 2025), but these scale poorly with field complexity due to expression swell. For a scalable approach, the only avenue is numerical.

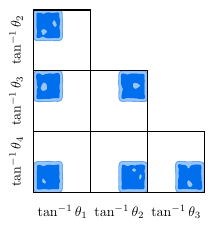

As a simple example, linear gravity is described by the Lichnerowicz theory in the metric perturbation \(\TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}}\), and this may be extended with a tuned Fierz–Pauli term to form the linearisation of massive gravity \begin{equation}\label{eq:FP}\begin{aligned} \Lag &= \Coupling{_1} \bigg[ \frac{1}{2} \PD{_\beta}\TensorField{} \PD{^\beta}\TensorField{} - \PD{^\alpha}\TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}} \PD{^\beta}\TensorField{} \\ &\quad - \frac{1}{2} \PD{_\gamma}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} \PD{^\gamma}\TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}} + \PD{_\beta}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} \PD{^\gamma}\TensorField{_{\alpha\gamma}} \bigg] \\ &\quad - \Coupling{_2} \bigg[ \TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} - \TensorField{}^2 \bigg]. \end{aligned}\end{equation} Since the theory parameters (collectively \(\Coupling{}\)) are a priori unconstrained, it is convenient to compactify the parameter space to a two-dimensional hypercube in \(\tan^{-1}\Coupling{}\). A posteriori, we know that the no-ghost and no-tachyon conditions following from \(\ \eqref{eq:FP}\ \) are \begin{equation}\label{eq:FP_unitarity} \Coupling{_1} < 0, \quad \Coupling{_2} > 0,\end{equation} and a numerical implementation of polology confirms this on the hypercube, as shown in Figure 1.

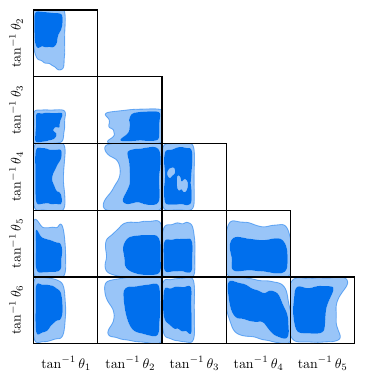

As a marginal extension of \(\ \eqref{eq:FP}\ \), we may consider the Fierz–Pauli–Proca theory, which adds a massive vector field \(\VectorField{_\alpha}\) through the Lagrangian \begin{equation}\label{eq:FPP}\begin{aligned} \Lag &= \Coupling{_3} \bigg[ -\frac{1}{2} \PD{_\alpha}\VectorField{_\beta} \PD{^\alpha}\VectorField{^\beta} + \frac{1}{2} \PD{_\alpha}\VectorField{^\alpha} \PD{_\beta}\VectorField{^\beta} \bigg] \\ &\quad - \frac{1}{2}\Coupling{_4} \VectorField{_\alpha}\VectorField{^\alpha}. \end{aligned}\end{equation} The combined unitarity conditions for \(\ \eqref{eq:FPP}\ \) are \begin{equation}\label{eq:FPP_unitarity} \Coupling{_1} < 0, \quad \Coupling{_2} > 0, \quad \Coupling{_3} > 0, \quad \Coupling{_4} < 0,\end{equation} and Figure 2 shows that these, too, are easy to find.

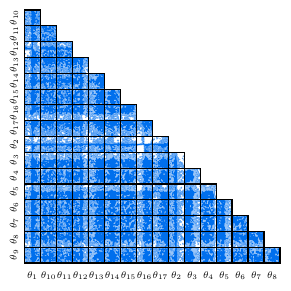

Whilst \(\ \eqref{eq:FP}, \eqref{eq:FPP}\ \) are well known models, we may use the same technique to study new theories, in which sectors are mixed. The most general Stueckelberg extension of massive gravity in which transverse diffeomorphism invariance is restored by the addition of an extra scalar \(\ScalarField\) is \begin{equation}\label{eq:TDiff}\begin{aligned} \Lag &= \frac{\Coupling{_1}}{2} \TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} + \Coupling{_5} \TensorField{}^2 + \Coupling{_6} \TensorField{} \PD{_\alpha}\VectorField{^\alpha} \\ &\quad - \Coupling{_6} \TensorField{} \PD{_\alpha}\PD{^\alpha}\ScalarField - \Coupling{_1} \PD{_\alpha}\VectorField{^\alpha} \PD{_\beta}\VectorField{^\beta} \\ &\quad + \Coupling{_1} \PD{_\beta}\VectorField{_\alpha} \PD{^\beta}\VectorField{^\alpha} + 2\Coupling{_1} \TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} \PD{_\beta}\PD{_\alpha}\ScalarField \\ &\quad - 2\Coupling{_1} \TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}} \PD{^\beta}\VectorField{^\alpha} + \Coupling{_2} \PD{_\beta}\TensorField{} \PD{^\beta}\TensorField{} \\ &\quad + \Coupling{_3} \PD{_\alpha}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}} \PD{_\gamma}\TensorField{_\beta^\gamma} + \Coupling{_4} \PD{^\beta}\TensorField{} \PD{_\gamma}\TensorField{_\beta^\gamma} \\ &\quad - \frac{\Coupling{_3}}{2} \PD{_\gamma}\TensorField{_{\alpha\beta}} \PD{^\gamma}\TensorField{^{\alpha\beta}}. \end{aligned}\end{equation} The theory in \(\ \eqref{eq:TDiff}\ \) is parameterised by a six-dimensional hypercube: the numerical polology in Figure 3 reveals a sizeable unitary volume, containing an extra massive scalar of spin zero. Formally, the bounds of this region can be obtained by a straightforward but lengthy analysis, and are found to be \begin{equation}\label{eq:TDiff_unitarity} \begin{gathered} \Coupling{_1} < 0, \quad \Coupling{_3} < 0, \quad \Coupling{_5} < \frac{-\Coupling{_1}^2 + \Coupling{_1}\Coupling{_6} - \Coupling{_6}^2}{6\Coupling{_1}}, \\ \Coupling{_2} > \frac{2\Coupling{_1}^2\Coupling{_3} - 2\Coupling{_1}\Coupling{_3}\Coupling{_6} - 6\Coupling{_1}\Coupling{_4}\Coupling{_6} - \Coupling{_3}\Coupling{_6}^2}{12\Coupling{_1}^2}. \end{gathered}\end{equation} For cosmological phenomenology, only the renormalised values of the \(\Coupling{}\) are interesting. The point is that a well-explored unitary posterior of these \(\Coupling{}\) is overwhelmingly cheaper to obtain, as compared to rejection-sampling dependant on formal conditions such as in \(\ \eqref{eq:TDiff_unitarity}\ \).

The theory in \(\ \eqref{eq:TDiff}\ \) is inflated with spurions, but for genuine gauge symmetries the concept of unitary volumes is also critical. In general, the parameter space will not contain volumes, but rather unitary hypersurfaces of lower codimension: only when these hypersurfaces are associated with the emergence of new gauge symmetries are they expected to be stable against radiative corrections. Modern sampling techniques happen to be well-suited to finding such features. To illustrate this, we consider the completely general parity-preserving tensor–vector–scalar theory, which has 17 free parameters. The bulk of the parameter space is sick, but by treating unitarity violation as a likelihood penalty we are naturally driven to the healthy features, as shown in Figure 4.

Implementation

Focussing on the sector of spin \(J\) and parity \(P\), the wave operator in a basis of spin projection operators is denoted \(\WaveOperatorJP{J}{P}\), where \(k\equiv\sqrt{\tensor{k}{_\alpha} \tensor{k}{^\alpha}}\) is the momentum. For general \(k\), this admits a collection of null eigenvectors \(\WaveOperatorJP{J}{P}\cdot\NullVector{J}{P}{a} = 0\) which encode all the gauge symmetries acting on the \(J^P\) sector. Once the \(\theta\) are sampled, these symmetries may be computed numerically from a polynomial expansion \begin{equation}\label{eq:PolyExpansions}\begin{aligned} \WaveOperatorJP{J}{P} &= \sum_{n} \WaveOperatorJPn{J}{P}{n} k^n, \\ \NullVector{J}{P}{a} &= \sum_{n} \NullVectorN{J}{P}{a}{n} k^n, \end{aligned}\end{equation} which gives rise to a block singular value decomposition problem. The gauge-regularised wave operator \begin{equation}\label{eq:RegularizedWaveOperator} \RegWaveOperatorJP{J}{P} \equiv \WaveOperatorJP{J}{P} + \sum_a \NullVector{J}{P}{a} \cdot \NullVectorConj{J}{P}{a},\end{equation} then defines a polynomial eigenvalue problem in \(k\), which yields a candidate spectrum of masses \(k^2=m(\theta)^2\). Because the construction in \(\ \eqref{eq:PolyExpansions}\ \) does not give rise to normalised \(\NullVector{J}{P}{a}\), this spectrum will generally be polluted by spurious ‘gauge’ masses, though these are readily stripped by comparing their null eigenvectors with the gauge sector of the kernel. The physical masses \(m(\theta)\) are associated with null eigenvectors \(\RegWaveOperatorJPm{J}{P} \cdot \PhysNullVector{J}{P}{s} = 0\), for which the condition \begin{equation}\label{eq:NoTachyon} m(\theta)^2 > 0,\end{equation} is the usual no-tachyon criterion.

A viable no-ghost criterion is known from (Barker, Marzo, and Rigouzzo 2024) to be \begin{equation}\label{eq:MassiveNoGhost} \NewRes{k^2}{m(\theta)^2}\left(P\,{\rm tr}\,\MoorePenroseJP{J}{P}\right) > 0,\end{equation} where \(\MoorePenroseJP{J}{P}\) is the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse of \(\WaveOperatorJP{J}{P}\). Even with sampled \(\theta\), obtaining the pseudoinverse remains a symbolic problem. For a numerical alternative, we consider the matrix \(\GaugeMatrixJP{J}{P}\) whose columns are the \(\NullVectorm{J}{P}{a}\), and which defines the non-gauge projection \begin{equation}\label{eq:GaugeProjection}\begin{aligned} &\ProjNullVector{J}{P}{s} \equiv \\ &\qquad \left[ \mathsf{1} - \GaugeMatrixJP{J}{P} \left( \GaugeMatrixJPConj{J}{P} \GaugeMatrixJP{J}{P} \right)^{-1} \GaugeMatrixJPConj{J}{P} \right] \cdot \PhysNullVector{J}{P}{s}, \end{aligned}\end{equation} of the massive null eigenvectors. The no-ghost condition in \(\ \eqref{eq:MassiveNoGhost}\ \) is then equivalent to \begin{equation}\label{eq:NoGhost} P \, \ProjNullVectorConj{J}{P}{s} \cdot \biggl( \sum_{n} n \, \WaveOperatorJPn{J}{P}{n} m(\theta)^{n-1} \biggr) \cdot \ProjNullVector{J}{P}{s} > 0,\end{equation} by a Kato expansion.

The criteria in \(\ \eqref{eq:NoTachyon}, \eqref{eq:NoGhost}\ \) may thus be reached entirely by numerical linear algebra operations, once the \(\theta\) is sampled. An initial, light per-theory application of computer algebra is required only to extract the symbolic \(\WaveOperatorJPn{J}{P}{n}\), and this problem was previously solved for any theory by the Wolfram Language implementation in (Barker, Marzo, and Rigouzzo 2024; Barker, Karananas, and Tu 2025).

Given the \(\WaveOperatorJPn{J}{P}{n}\) matrices, the Julia language is a naturally performant choice for numerical polology; a sampler explores the compactified \(\theta\) hypercube, and an evaluator uses optimal BLAS/LAPACK routines to probe the spectrum at each point.

The central importance of sampling allows a natural connection to established precision cosmology workflows. The unitary posterior may be exported in the standard GetDist format, as visualised in figure. These posteriors may be ingested by pipelines which probe any other phenomenology sensitive to the free \(\theta\); we will see presently that a wealth of such probes are already in mainstream use, and that for the most part they are needlessly restricted to simple field content.

Sampling, by itself, admits many variants. For the current implementation, we use a nested sampler with a likelihood \(\mathcal{L} = \prod_{m(\theta)} u_{m(\theta)}\), where \begin{equation}\label{eq:SoftLikelihood} u_{m(\theta)} \equiv \begin{cases} 1 & U_{m(\theta)} > 0, \\ e^{\l U_{m(\theta)}} & U_{m(\theta)} \leq 0, \end{cases}\end{equation} and the \(U_{m(\theta)}\) correspond — across all \(m(\theta)\) — to the left hand side of the inequalities in \(\ \eqref{eq:NoTachyon}, \eqref{eq:NoGhost}\ \). The penalty for unitarity violation is set by the scale \(\lambda\).

Unitarity, computed in this way, is exceptionally lean; the compiled evaluator has a millisecond runtime, three orders of magnitude faster than modern Boltzmann solvers. This is to be compared to symbolic computation, which can take many hours when parallelised on a cluster. In turn, this economy facilitates the large \(n_{\text{live}}{}\sim 10^4\) used in figure, which is necessary in practice to resolve the fine structures associated with particle physics requirements — by contrast, phenomenological constraints on cosmological parameters are often smoother, and more amenable to kernel density estimation.

The unitarity evaluator is also extensible to a more comprehensive science stack; current by-products include the gauge symmetries and particle masses, but explicit cutoffs can also be computed.

Astroparticle physics

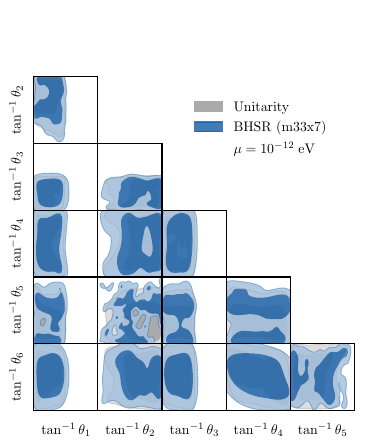

The derived quantities associated with the science stack admit various phenomenological constraints, which can be applied as multiplicative weights to the unitary posterior. We demonstrate this using three independent probes, applied to the theory in \(\ \eqref{eq:TDiff}\ \).

Ultralight bosons trigger superradiant instabilities of spinning black holes, so the observation of a rapidly spinning black hole excludes boson masses within a corresponding window (Arvanitaki, Baryakhtar, and Huang 2015). We use precomputed exclusion tables for M33 X-7 (Orosz et al. 2007), a stellar-mass black hole probing \(m\sim 10^{-13}\)–\(10^{-11}~\mathrm{eV}\). The survival probability provides a smooth weight in \([0,1]\) for the spin-\(0^+\) scalar mass. As shown in Figure 5 (left), superradiance excludes \(63.8\%\) of the unitary posterior, carving characteristic exclusion bands from the coupling space.

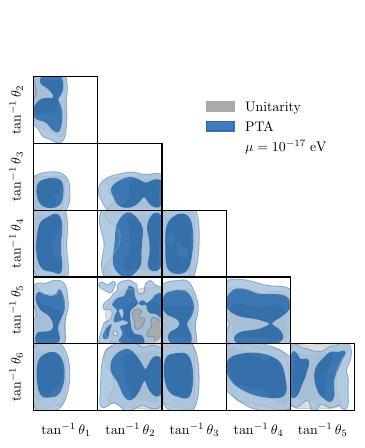

Stochastic fluctuations of an ultralight dark matter field induce correlated timing residuals in pulsar arrays (Kim and Mitridate 2024). The NANOGrav 12.5-year dataset places an upper bound on the local dark matter density as a function of the scalar mass, with peak sensitivity at \(m\sim 10^{-17}~\mathrm{eV}\). Assuming a local overdensity of \(\rho/\rho_0 = 5\times 10^4\), the PTA constraint excludes \(95.8\%\) of the posterior, as shown in Figure 5 (right). At the standard local density (\(\rho = \rho_0\)), current PTA data does not exclude any masses.

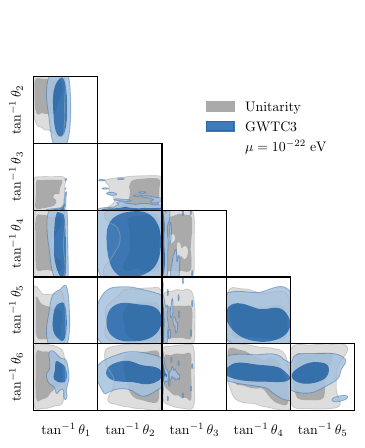

A massive graviton modifies the dispersion relation of gravitational waves, causing frequency-dependent propagation speeds that are detectable in compact binary coalescence signals (Abbott et al. 2025). The GWTC-3 combined analysis of 43 binary black hole events yields the bound \(m_g \leq 2.42\times 10^{-23}~\mathrm{eV}\) at \(90\%\) credibility, surpassing the Solar System ephemeris bound of \(3.16\times 10^{-23}~\mathrm{eV}\) (Bernus et al. 2020). Unlike the scalar probes above, this constrains the spin-\(2^+\) graviton mass. As shown in Figure 6, the GWTC-3 bound excludes \(20.1\%\) of the posterior.

These constraints are composable: since each acts as an independent multiplicative weight, they can be applied sequentially to produce joint posteriors combining unitarity with any subset of observational probes.

Extensions

The functionality shown above is illustrative, and many extensions are possible.

The high dimensionality of the \(\theta\) space, and convoluted shape of the physically significant regions, are well suited to nested sampling. Unitary volumes are currently represented by likelihood plateaus, which are known to be difficult for samplers to explore. In all cases, it is the boundary of lower-codimension features which are of physical interest: unitary volumes are defined by such boundaries (so long as one picks the correct side), much like emergent gauge symmetries. This understanding shifts the focus to developing more sophisticated likelihood penalties for unitarity violation.

An associated problem is the lack of a physical measure on the \(\theta\) hypercube. It is interesting to consider whether the derived quantities, such as masses, can help to define such a measure. The \(\theta\) parameterisation is also arbitrary, and follows from the conventions in (Barker, Marzo, and Rigouzzo 2024; Barker, Karananas, and Tu 2025). A more natural parameterisation factors out mass dimensions, with parameters of common dimension spanning hyperspheres. Moreover, the full processing of a given model is hierarchical: gauge hypersurfaces, where identified in a parent theory, give rise to constrained models, and so on. These models are numerically discovered and numerically defined, which is a property that the original parameterisation does not share. It becomes necessary to either reverse-engineer the constraint (for example, via symbolic regression), or to soften the physical properties of the science stack in a way that remains stable as child-theories are discovered at increasing depth.

By design, the phenomenological plugins are arbitrarily extensible. Here, we have illustrated the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of mass exclusions. These serve to constrain the model, but they do not help us to alleviate tensions. For the pipeline to be used in this way, the derived quantities must lead to large scale structure and microwave background predictions which require per-parameter inference.

Extensions to the science stack are intended to work in tandem with phenomenological constraints. It is expected that relevant theories will provide new, light species of interest in cosmology. An extended stack will constrain the interactions so as to suitably reduce quantum corrections to this stack. Constrained interactions will then feed back into the phenomenology, and so on.

There are two less ambitious extensions to the science stack. Firstly, the inclusion of the massless sector has so-far been worked out only analytically: a numerical implementation is obviously necessary, since new massless degrees of freedom are probably unacceptable. Secondly, we note that extension to fermionic fields is straightforward, though tedious, and that the same is probably true for internal symmetries.